The light changes: red for the cars, a little green walking man for us pedestrians. Then the little man changes into numbers: 30, 29, 28, 27 … It takes me a minute (ha!) to realise that I’ve got less than ten seconds to cross. And here I was, thinking the machine was counting people crossing. In reverse. Maybe only so many are allowed to cross the street? Someone behind me tutts loudly, then swishes past and mutters It’s gone green, moron. I start to tell him that yes, I am indeed a bit out of it, but he’s disappeared somewhere in the marching crowd.

I wonder where they’re all going. They’re all in a hurry.

I’m not. Or rather, I should be. Lunch with my sister in some café in the QVB. She’s texted me the name, twice, and the time. But I’m a bit lost.

Or maybe it’s just that I don’t want to see her. She can be a bit of a pain.

The noise behind me, around me, is cluttered. Trucks reversing, brakes screeching, cranes creaking. A forklift moans like a banshee. It’s chilly today, but the air’s dusty – the sun’s complaining about all the construction going on. Another hotel, another shopping mall? I have no idea. I half-cough then quickly cover my mouth – covid guilt! As I breath through a tissue (I left my mask at home, dammit) I notice another sound, like a lamb bleating. Wouldn’t that be weird, a sheep in the middle of the city; perhaps I’ve gone back through time, perhaps I’m in Dickensian London. Hallo, is that Oliver Twist I hear, my good man!

But a dirty yellow bulldozer swerves into a driveway nearby and the dust goes mad again and I don’t think Victorian Britain would ever have been this noisy.

Again the bleat. Now I see what it is – on the footpath, almost camouflaged against a grubby brown barricade, underneath a grubby brown temporary and very flimsy portico (I’m not sure how the council approved that), sits a guy begging. His hand’s out, he’s asking for money for something – I can’t understand what – and his other hand is resting on a dog. The dog’s wearing a coat, but the poor guy is only in a t-shirt and ripped trackies. Why is he sitting here in such a noisy cold dusty spot?

He’s not the first I’ve seen today. Before I headed for the bus stop I filled my pockets with coins. I’ve handed out most of them already. Not that 50c or 20c coins will really help any of the beggars I’ve passed but they all say thank you, smile gratefully. I want to tell them that I’d give them more money if I could but if I said that I’d sound like a right wanker.

That’s what’s kept me late, I suppose. My father saw me picking spare change from a box on my dresser and demanded to know what I was doing. I told him I’d give it to people that need it and he yelled Put it back, you’ll never know when you might need it, and I said that I really didn’t need 20c coins, it can’t buy anything, not these days, and banks probably wouldn’t let me deposit a few dollars’ worth of pennies anyway.

Argument ensued. He rabbited on about how those homeless bastards in the city were scamming the system, that they were actually rich people who got richer by taking dollars from silly, innocent people like me.

But, I told him, I read that 1 in 3 vagrants have mental health issues. And then there’s the ones who’ve suffered beatings by their parents or spouse, or’ve been kicked out, or have lost their jobs and their homes. Why would you embarrass yourself or live in cold and filth if you’re rich?

I mentioned the old man I saw spat on by a guy in a suit. And the woman with her swollen purple legs stretched across the footpath that a girl tripped over. The girl swore like crazy at the poor woman, told her to get her fat arse off the street and get a job.

Some of them have mobiles! yelled Dad. You’re not poor if you’ve got one of those. And how do they feed their pets, eh? That bloke with the parrot on Pitt Street – it’s all a gimmick, a way to rip off honest people.

I know my sister secretly agrees with Dad. She always pretends to be big-hearted, understanding, holier-than-thou, a regular Mother Theresa. But I saw her pinched face when a vaguely smelly guy asked her for money for food outside the cinema near her house.

I step around a few people, bump into a girl in stilettos whose face is stuck to her phone, and drop some change into the guy’s hand.

He has the saddest face I’ve ever seen, even when he smiles his thank you. A face that sends a quick jolt through my spine. I can’t think of anything unwanky to say.

He reminds me of someone.

Nice dog, I eventually blurt.

My best mate, he says, and kisses the dog.

He looks healthy, I say, then regret it immediately. It was like I’d said the man looked unhealthy in comparison.

She is, he says eagerly, grinning. But his eyes are pearl-black and wet. Her name’s Fear.

I drop a dollar in the can beside him. More guilt – now he’ll think he only got it because I feel sorry for him. Which I do. But I don’t want him to know.

You have a good day in the city, he beams.

Not sure I will, I say. Fear is licking my hand and I can’t make myself leave. Cold people bustle around me and the dog’s tongue is strangely warm, though a little bit gross.

I’m off to the Public Trust Office, I say. Not the happiest part of town. (Again I wince. More stupid words! As if he’s happy here!)

You’re making a will? he says.

Yes, I ask, surprised.

You look sort of young.

If only, I think.

I’m a bit lost, I say. He points up the street. It’s just a few blocks. Just head straight up there.

Have you made a will? I ask (!!!!).

Ha, he laughs, miserably. Once I might’ve, but not now.

I nod, as if knowingly. I’m not gonna dare ask. Well, I say, I should head off now. My sister’s waiting. You know.

(As if he knows!)

I had a sister, he blurts.

Oh! I say lightly. Where is she?

Not here anymore, he says. His words are so soft I can barely hear him over a police siren, but I hear them. I consider asking him about her but his eyes are dim and he seems to have forgotten me.

I rub Fear’s head and say goodbye. I can’t for the life of me work out who the guy reminds me of. Definitely not anyone I know. Definitely not my father.

This morning Dad yelled at me for not getting a proper job, for giving in to lying underdogs. You’re bloody stupid for a doctor, he snarled. Don’t you understand anything?

I’m not a doctor, Dad, I muttered. I’m a historian. A historian interested in history’s underdogs. Convicts. And you’re right, I understand nothing. Not why people suffer road rage. Not why churches burn down. Not why studying an Arts degree costs so much these days. Not why Russia invaded Ukraine. Not why children get fined for breaking covid restrictions. I’ve learned how to research, yes, but I’ve got no idea why humans do the things they do. Why mothers have to die.

One of the things I miss is that Mum could always control Dad. A few times I heard her having a go at him for his silly views – but in the kindest voice. Practical but loving. A voice he didn’t argue against. She tried to explain him to us, said he’d changed over the years, was nowhere near as closed-minded as he now was. Why does he have to be like that? I’d asked. She sighed. Because when you focus only on work, as he does, it’s hard to take in the world. I asked how she came to like him. She said she knew his brain was much wider than that – that it could push open windows and stare far beyond when it wanted. He just needed encouragement; he just needed to stop thinking about his goddam work. His eyes, she said, she could see his tolerance, his curiosity there.

I agree. I’d seen that sensitivity when the little boy next door asked Dad to fix his bike. But since her death his eyes have shut down. He refuses to open any windows.

I finally find the café at the QVB after a series of texts and angry emojis from my sister. Right on the top floor, very fancy, filled with old people. Megan’s wearing pearls; she’s tapping her red nails on her phone.

Her questions are the same as usual. How’s Dad when are you moving out he doesn’t need you anymore are you paying rent have you got a real job yet why are you still at uni how’s your love life ha ha. She asks if I’m working on my next doctorate and doesn’t wait for an answer while she waves to the waiter and orders a glass of shiraz for both of us. I’d thought of popping into the State Library while in the city and delving once more into original documents concerning the treatment of Sydney convicts by landowners. I liked the library’s serenity, the smell of its diaphanous original maps of Port Jackson and receipts for sheep and forced labour and sketches of Aboriginals with woomeras but my brain really isn’t working today. (In fact, it had seemed to have stopped working properly for some time now, slowing down at Brexit/ Trump/ Morrison/Orban /Erdogan /dictators dictators dictators more dictators. Then it numbed entirely at Mum’s death. I knew Mum’s death was ill-fated; the fires, the pandemic, the floods, the neverending deaths in custody…They all occurred and then she died.) So I’m not sure I’ll make it to the library today. If I got lost in King Street this morning I’d certainly get lost in the library’s bowels.

What are you up to? Megan asks again.

I’m just having lunch with you.

Well. You look somewhat – dressed up.

After a few mouthfuls of wine I blurt out why I’m in the city.

You’re making a will? she scoffs. What on earth for? And who the hell would you leave your estate to? You’re not exactly in a relationship. Or is there something you’re not telling us?

I don’t intend to tell her that even though I’m not in a relationship I don’t want Dad or her kids or any of our family to get my savings. They’ve all got plenty. I will never tell her that I’m planning to give it all to charity.

You’re not leaving it to some useless charity, are you? she says.

She sees the look on my face and tells me not to be an idiot. I don’t tell her how much I liked that dog that licked my hand, Fear. And her owner. That I’d rather be with him outside the rackety construction site than in this stiflingly twee café.

What’s wrong with leaving some of it (I lie) to, I don’t know, the homeless, say?

None of them deserve it, she says. I know you feel sorry for them. But most of those lot are greedy. They and their cohorts are just as likely to rob you blind when you’re doling out your cash to them. Look out the window. She points down to George Street. That bloke has been in that doorway every day this year. I see him when I go to work and when I leave. He must’ve made a fortune by now. Would you believe he’s got a phone. So he’s obviously not poor. She shakes her head. Too many con artists in this world.

We kiss goodbye, I automatically send my love to her well-fed children, then I walk back to King Street and on to O’Connell Street. I can see Fear on the footpath, but his owner has vanished. Why leave the dog there?

I’m thinking about this the whole time at the Public Trust Office. I’m finding it hard to concentrate. The young solicitor tells me that my family members could potentially have a claim against my estate if I leave it to a charitable institution. Would that matter if I’m dead? I say; at least I wouldn’t have to appear in court. She smiles. I tell her that I just want to leave it to the homeless and she says I need to pick an actual charity. I ask her to name one and she says it’s up to me – she can’t make suggestions as to potential beneficiaries.

I could tell the solicitor wanted to ask why I’d deny my family my feeble savings, and leave my estate to the homeless. It was to do with Mum – my mother, a woman born into a wealthy North Shore family (but fell in love with and married a depressingly parsimonious salesman) had always helped poor people. I went with her every year to Martin Place at Christmas to help feed the destitute and hungry. Dad always wanted to know why did she did that, why she helped the poor so much. Does it matter? was her answer. Dad was born without much and toiled all his life, building and protecting his business. He believed everyone should work hard, and drove me to McDonalds when I was 14 to get a part-time job. He’s kept every cent he’s ever made, has a stern distrust of accountants, taxmen, lawyers and vagrants, and still can’t understand why Mum donated to charity.

On the PTO’s steps a beggar holds out a grubby hand and asks me for money. I’ve no more coins in my pocket so I pull out my purse but all I have is a credit card and a $50 note. I’m so sorry, I murmur, next time I promise. The beggar nods politely and turns away.

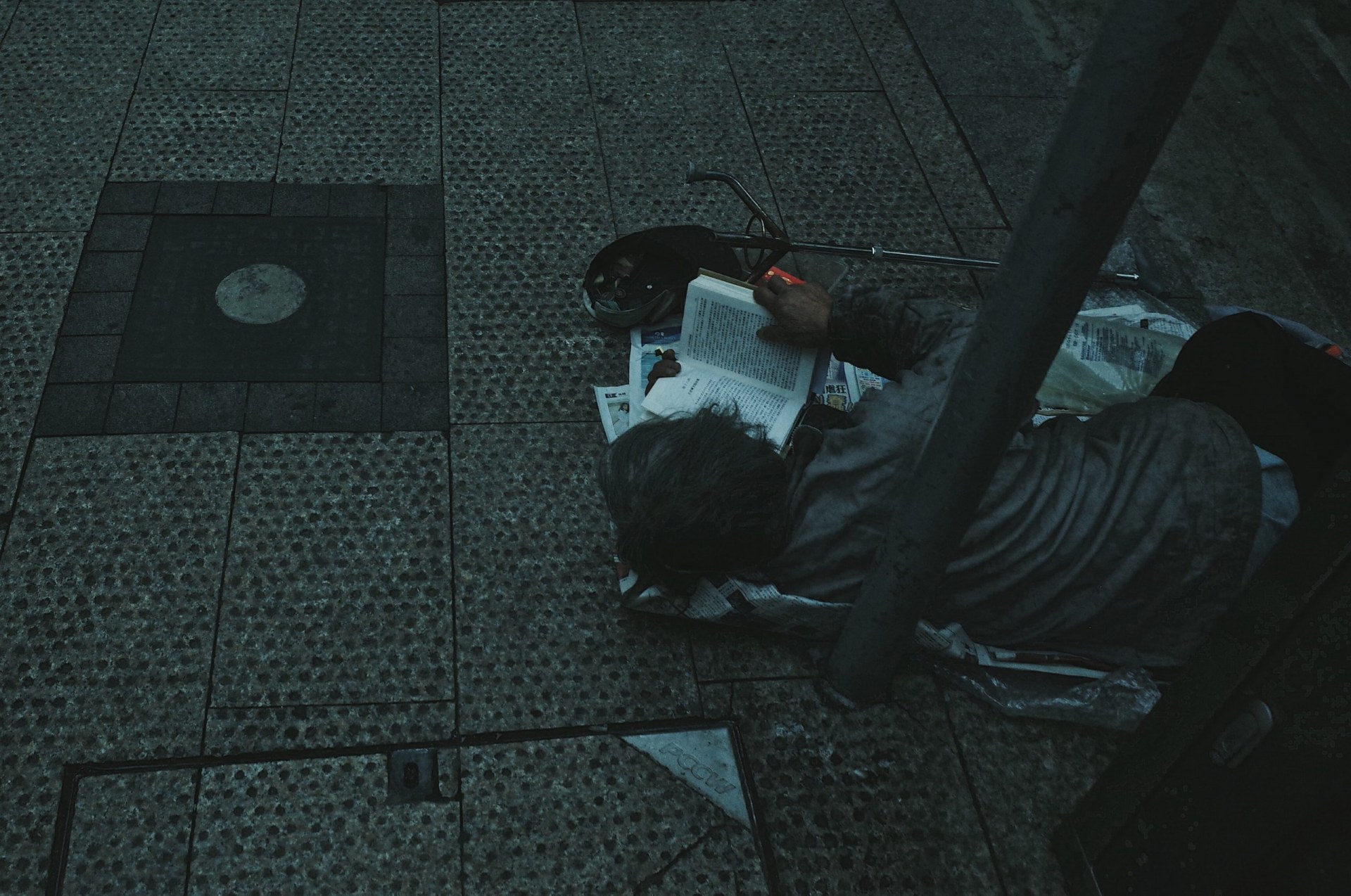

My fear about Fear’s owner has grown and I find myself striding towards King street. Fear woofs when she sees me, wags her tail wildly, and I see now that the owner is curled under a tatty grey blanket, lying on the remnants of a sleeping bag – the cement must be freezing underneath. For some reason a piece of old shining red cloth works as a sheet. For some reason that shiny red cloth breaks my heart. Colourful badges are pinned to the sleeping bag. Maybe he’s a bowerbird. He opens his eyes, looks at me in a kindly way, but is obviously bemused.

What’s your name? I ask too loudly.

Before long I’m sitting on his milk crate. Turns out Elijah was studying first- year modern history at Sydney Uni when he crashed his car. His sister died; the damage to his leg led to an addiction to painkillers, and his family kicked him out when he was caught stealing meth.

Same old story, he whispers, and nods at another mendicant under a bank’s portico across the road.

I realise suddenly who he reminds me of. A child who lived right near here, 200 years ago, in a convict hut of wattle-and-daub; a boy whose mother was transported to this dismally remote island for stealing a roll of silk fabric – a roll of red, I imagine, like this guy’s sheet. Bizarrely she’d been allowed to bring her three children. But all had died here, near the Rocks, the mother included, except for the boy. He’d become a bushranger, in the faraway south-west, hanged by the neck when he was 17. I’d recently seen a rough sketch of him in a prison museum near Dalton. Gaunt and gangly, but with pearl-black wet eyes. Like Elijah. Like my Mum.

Not the best of lives.

I have an idea, I say.

Dad’s out when I return home with Elijah, thank god. I take him up to Mum’s old sewing room. Apart from working for charities and being an ace accountant Mum spent a lot of time embroidering handbags and selling them at the local Saturday markets. Sometimes she even took them to Paddington markets – she could charge more for them there, and donate the money to Amnesty or Ted Noffs. She was a bit of a hippy, really, in what she wore, what she believed, how she tied scarves around her hair and burned incense. Dad seemed to forgive her for all of it; it’s a damn shame he wants to wipe away what’s rubbed off from her onto me.

Elijah is in awe of the posters, the embroidered works of art, the books lining Mum’s little room. He sits on the bed and bounces it slightly and grins.

I take him downstairs and make him some dinner, than suggest politely that he takes a shower. (I don’t want Dad smelling him as soon as he opens the front door.) I get some trousers from Dad’s room and give Elijah one of my XXXL tshirts and a sloppy joe. He’s so scrawny they all billow around him.

We both sit in his new bedroom – Mum’s room – and roll a small rubber ball for Fear to play with. I can tell Elijah’s ready to sleep. I say goodnight and close the door and squat in front of the tv in the lounge room. I’m finding it hard to sit still; I pour a glass of whiskey and flick through the channels. I can feel Dad approaching, his headlights searching the street, the car being parked in the driveway, his feet clapping impatiently on the stones to the front door, his key in the lock.

This is not going to be easy.

Photo by Dynamic Wang on Unsplash