It was my first time. The rifle was slippery in my fingers, and Jojo laughed when I nearly dropped it. I’d seen many before, but never held one. Mr General smacked me over the head: Get with it boyo.

Call it a name, he said. Then it will be yours. You are responsible for it, you are its mother and father, its friend, its owner. Lose it, break it, and you will be punished.

We stood the rifles beside us – mine came up to my shoulder. But I clung onto its hard wood, got to know its trigger and lock and armrest, and we were comrades.

After Mr General’s men had sliced Mama in our rice field then speared and padlocked my father’s lips (it was important they said that Papa not reveal their whereabouts to the army) I was told to march with the other children. With the heavy sack of grain they tied to my back it was a difficult week keeping up, but after the boy lagging behind me was kicked into a fire I was careful to drag my sore legs quickly. At the camp we each stood before Mr General. ‘We’re going to write your name,’ he smiled. I waited for him to take out a pen, but instead he nodded at three boys, a bit older than me. Their half-closed eyes rolled white, they seemed distracted, vague. They beat me with large clubs until I twisted in my blood and shit and couldn’t see anything properly – If you scream, we’ll kill you, the commander said. So I didn’t. So I couldn’t.

Three days later the swimming world began to solidify – I saw the tent’s stained flaps, felt the coarse pallet beneath me. My lips were cracked and the blood was stale in my mouth. I refused to cry out, but couldn’t stop lowing like a sick calf. I know I called for Mama. The flies buzzed endlessly at my skull.

An officer and a man in strange clothes appeared. After giving me sundried sweet potato the man mixed shea oil and egg and water in a bowl, then painted it in a cross on my head, lips, hand and heart. You’re no longer unclean, he said. They gave me a hot, bitter drink; it made me dizzy but for the first time in weeks I slept like the dead.

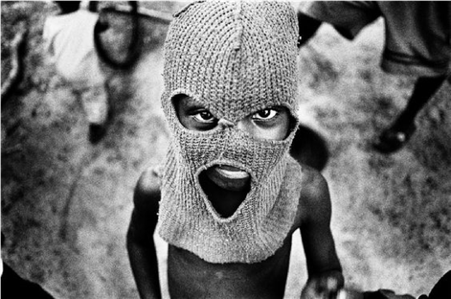

We practised for a month. At first with machetes, axes and clubs, then the rifles. At night we’d go with Mr General into the dirty underarm of the jungle and learn to see in the blackness. Learn not to be scared of the hisses and growls, the clicking and roars. Learn to target and hit the man.

Afterwards they fed us porridge and beer, and we took our medicinals. The navy sky would twirl then, and I’d watch a million stars smile upon me, a million planets wave past. Sometimes Mama would smile at me and I’d reach up high and try to touch her. It wasn’t a bad feeling. I came to want that feeling more and more. Then one dawn Colonel Ram saw tears on my face. If you think of home you will die, he said, we are your family now. He whipped my back with a thorny shoot until my school shorts were as ripped and red as the sun. The medicinal juice clouded the pain, and I learned to block Mama, Papa, my sisters and brothers. I thought only of my true family. The Lord’s Resistance Army.

At my first blooding I used a bayonet. A kid had tried to escape but was caught by her brigade and dragged back to camp. We, the new recruits, were all forced to stand in a circle around her. Like me the others were hungry – I could see it in their dead eyes, their bloated bellies – and exhausted after marching for days. But we dared not move, dared not question the naked dust-covered girl. She floundered like a ragdoll, her thighs and privates splattered rust-red from being invaded by many soldiers. Mr General ordered us to pick a weapon, then we each slashed at her until she was cut into pieces and her blood slithered in a thick river around our feet. When Jojo hacked the machete into her chest she gurgled, and died; as we covered her in soil I could not look into his eyes.

Now I was part of them. The next morning my rifle was sprinkled with the holy water and we marched into the jungle. When Mr General imposed his strange, ill-omened orders, I clenched my eyes tight and prayed to his spirits to give me courage. It seemed wrong to damage men so.

We hid behind the monstrous canopy trees, not breathing. A strangler fig waved slightly in the steamy breeze and I waited for the world’s end. I saw movement and fired – I’d killed the enemy, a tall skinny boy with deeply scarred cheeks. I took his hatchet and cut off his balls. After the battle we screamed and bounced in victory, in relief.

Mr General and Colonel Ram were pleased – in performing their command we’d filled three plastic wash basins with testicles. They awarded us extra soup and we ate silently under the sultry mango trees. The powerful spirits, dark and keening in the tangled wilderness, were with us.